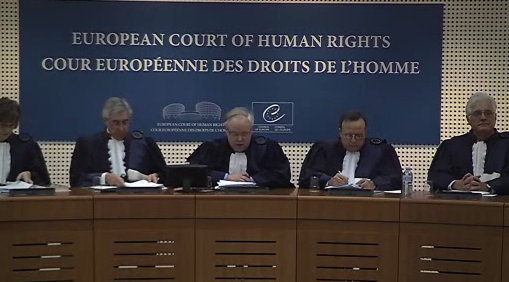

Credit: ECtHR

On September 16, the European Court of Human Rights delivered its Grand Chamber judgment in Hassan v. United Kingdom, which involved the detention of an Iraqi national, Tarek Hassan, by the British army in Iraq in 2003. The applicant alleged that the United Kingdom was responsible for Tarek’s unlawful detention, ill-treatment, and death. The key issues before the Court were whether the British army’s actions were brought within the Court’s jurisdiction through extra-territorial application of the European Convention on Human Rights and to what extent the surrounding context of international armed conflict modified the State’s human rights obligations. [ECtHR Press Release]

The Court held that there was no violation of the European Convention on Human Rights because, although Tarek was within the UK’s extra-territorial jurisdiction pursuant to Article 1 of the Convention, the Court interpreted Article 5 of the European Convention to allow for the otherwise unauthorized detention of suspected combatants, in keeping with the Geneva Conventions, in the context of international armed conflict. Because it found that Tarek’s detention complied with international humanitarian law and there was insufficient evidence linking his ill-treatment and death to the actions of the British forces, the Court rejected the applicant’s claims. See ECtHR, Hassan v. United Kingdom, [GC], no. 29750/09, ECHR 2014, Judgment of 16 September 2014, paras. 62–64, 80, 108–111.

Facts of the Case

The applicant, Khadim Resaan Hassan, lodged his application with the European Court on behalf of his brother, Tarek, who was found dead following his detention by British armed forces at Camp Bucca in Iraq. [ECtHR Press Release] Hassan had been a high-ranking member of the Ba’ath party, who went into hiding because the British army began arresting party members. In April 2003, the British army came to Hassan’s home in Basrah, and took Tarek away in the middle of the night. Hassan alleges that Tarek was taken as a hostage, while the UK contends that he was arrested as a suspected combatant and was released on or around May 12, 2003 when the UK determined that he was a non-combatant. Although Camp Bucca was a detention center operated by United States forces, British forces exercised control over inmates that they had arrested.

In September 2003, Tarek’s dead body was found in Samara, which is approximately 700 kilometers from Camp Bucca. See Hassan v. United Kingdom, Judgment of 16 September 2014, para. 20. Hassan alleges that Tarek’s body bore signs of torture and execution; he had many bruises, eight bullet wounds to the chest from an AK-47 rifle, and his hands were tied with plastic wires. [ECtHR Press Release]

Procedural Developments

Hassan originally brought his case before a British administrative court, seeking compensation, a declaratory judgment that his brother’s rights under the European Convention were violated, and an order requiring the UK to undertake an investigation into Tarek’s death. The court dismissed Hassan’s case on the grounds that the UK did not have jurisdiction because the United States operated Camp Bucca. [ECtHR Press Release]

On June 5, 2009, Hassan lodged his complaint with the European Court of Human Rights. Hassan asked the Court for a declaration that the British government violated Article 5(1–4) (right to liberty and security) on the grounds that Tarek’s arrest and detention were arbitrary and were not carried out in accordance with the law, Article 2 (right to life), Article 3 (prohibition against torture and inhumane or degrading treatment), and Article 5 for the State’s failure to investigate Tarek’s detention, treatment, and death. He also reiterated his request for compensation and an investigation into Tarek’s death. The Grand Chamber heard the case on December 11, 2013. [ECtHR Press Release]

Summary of the Judgment: Extra-territoriality and International Humanitarian Law

The first issue the Court addressed was whether the UK had sufficient control to consider Tarek within its jurisdiction. Under Article 1, State Parties to the Convention are responsible for “securing to everyone within their jurisdiction” the rights and freedoms contained in the Convention. See European Convention, art. 1. The UK argued that Tarek was not within its jurisdiction and, alternatively, that only international humanitarian law applied to the situation, meaning the facts could not give rise to a violation of the European Convention. See Hassan v. United Kingdom, Judgment of 16 September 2014, paras. 65, 76. Specifically, the government argued that extra-territorial jurisdiction cannot be found where, during an active hostilities phase of an international armed conflict, State agents are operating in a territory where they are not the occupying power. Id. at para. 76.

The Court rejected the UK’s argument that it lacked jurisdiction, recalling its decision in Al-Skeini, where it found that when the State operates extra-territorially and takes an individual into its custody, that custody is a basis for jurisdiction under Article 1 of the Convention even in the context of an international armed conflict. See Hassan v. United Kingdom, Judgment of 16 September 2014, paras. 76–77; ECtHR, Al-Skeini and Others v. United Kingdom, [GC], no. 55721/07, ECHR 2011, Judgment of 7 July 2011, para. 136. The Court held that Tarek was within the jurisdiction of the UK “from the moment of his capture” on “23 April 2003, until his release from the bus that took him from Camp Bucca to the drop-off point, most probably Umm Qasr on 2 May 2003.” See Hassan v. United Kingdom, Judgment of 16 September 2014, para. 80.

The second issue before the Court was how the relationship between international humanitarian law and the European Convention impacted the UK’s obligations. The UK argued that Tarek’s capture and detention did not violate the Convention because they occurred in the context of an international armed conflict and should be evaluated under international humanitarian law. See id. at para. 65.

Article 5 of the European Convention protects the right to liberty and security of person, and it forbids the deprivation of liberty except in specific circumstances. Although Article 15 of the Convention allows States to make derogations from Article 5 in times of war, the UK had not made any derogations here. See id. at para. 98.

The Court rejected the State’s contention that international humanitarian law should apply to the exclusion of international human rights law and held that the two bodies of law can, and should, be applied together, writing:

… to accept the Government’s argument on this point would be inconsistent with the case‑law of the International Court of Justice, which has held that international human rights law and international humanitarian law may apply concurrently (see paragraphs 35-37 above). As the Court has observed on many occasions, the Convention cannot be interpreted in a vacuum and should so far as possible be interpreted in harmony with other rules of international law of which it forms part (see, for example, Al-Adsani v. the United Kingdom [GC], no. 35763/97, § 55, ECHR 2001‑XI). This applies equally to Article 1 as to the other articles of the Convention.

Id.

The Court determined that the Geneva Conventions were applicable to the situation in Iraq, because they apply in situations of international armed conflict or occupation of the territory of a High Contracting Party, and all parties involved were High Contracting Parties. See id. at paras. 108–111.

The Court decided to interpret and apply the provisions of Article 5 “in light of the relevant provisions of international humanitarian law only where this is specifically pleaded by the respondent State.” Id. at para. 107. Essentially, the Court added an additional circumstance to those listed in Article 5(1), by interpreting Article 5 to permit States parties to deprive individuals of their liberty in times of international armed conflict, in a manner consistent with international humanitarian law.

The Court evaluated Tarek’s arrest and detention and determined that the British forces’ actions were consistent with the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions, which permit detention of individuals who the State reasonably believes are prisoners of war or threats to security. See id. The Court reasoned that Tarek’s arrest and detention were not arbitrary because he was found with weapons in the house, screened upon arrival in the detention center, and released after he was found not to be a threat. See id. The Court held that there was no violation of Article 5 because the State acted in accordance with the Geneva Conventions. See id.

The Court found the alleged violations of Articles 2 and 3 (right to life and the right to be free from torture and inhumane treatment) to be inadmissible for lack of evidence establishing that Tarek’s death and ill-treatment occurred while he was under the control of the UK forces or that they were responsible in any way. See id. at paras. 62–64. The Court noted that when State agents have contributed to the death or ill-treatment of an individual, the State has a duty to undertake an official investigation, but that the allegations here were “manifestly ill-founded” and did not give rise to such an obligation. See id.

Separate Opinion

While the Court ruled unanimously that the UK had jurisdiction and that there was no violation of Articles 2 and 3, the finding that there was no violation of Article 5 was split 13 votes to 4. In a partially dissenting opinion, Judge Spano, joined by Judges Nicolaou, Bianku, and Kalaydjieva, argued that the Court should give priority to the European Convention over the Third and Fourth Geneva Conventions. See ECtHR, Hassan v. United Kingdom, [GC], no. 29750/09, ECHR 2014, Judgment of 16 September 2014, para. 19 (partially dissenting opinion). They reasoned that the Convention applies in both peacetime and wartime, and the only proper way to derogate from Article 5 is through the Article 15 mechanism for formal derogation. See id. at paras. 2–9. They disagreed with the majority’s “accommodation” of international humanitarian law in this context, arguing that it has the same legal effect as the “disapplication” of the Convention’s safeguards, and that, in this case, Article 5 had been violated. See id. at paras. 18–19.

Additional Information

For additional information on the relationship between the European Convention and international humanitarian law as it applies to this case, see Marko Milanovic’s post on the Blog of the European Journal of International Law.

The European Court of Human Rights’ factsheets identify and summarize its significant decisions concerning Extra-territorial Jurisdiction and Armed Conflicts.

To learn more about the European Court of Human Rights, visit the IJRC Online Resource Hub.