WHAT ARE HUMAN RIGHTS?

Every human being is entitled to protection of, and respect for, their fundamental rights and freedoms. Human rights are those activities, conditions, and privileges that all human beings deserve to enjoy, by virtue of their humanity. They include civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights. Human rights are inherent, inalienable, interdependent, and indivisible. This means we have these rights no matter what, the enjoyment of one right affects the enjoyment of others, and every human right must be respected.

Based on their international commitments, governments are required to put in place the laws and policies necessary for protection of human rights and to regulate private and public practices that impact individuals’ enjoyment of those rights. Therefore, we think of national governments (“States”) as the guarantors, or violators, of human rights.

Human rights treaties protect individuals from government action (or inaction) that would threaten or harm their fundamental rights. Like national constitutions, which are covenants between governments and their citizens, international human rights treaties are covenants between States and the international community, whereby States agree to guarantee certain rights to everyone within their territory or under their control. When States ratify human rights treaties, they agree to both refrain from violating specific rights and to guarantee enjoyment of those rights by individuals and groups within their jurisdictions.

Regional and international human rights bodies monitor States’ compliance with their human rights commitments. These courts and oversight mechanisms also provide opportunities for redress and accountability that may be non-existent or ineffective at the national level.

Generally, States decide whether or not to ratify human rights treaties or to accept oversight by a monitoring body or court. The level of participation in the international human rights framework varies among States. IJRC’s quick reference chart identifies the mechanism(s) responsible for interpreting and applying each of the principal UN and regional human rights treaties, their competencies, and how many States are subject to their jurisdiction.

The driving idea behind international human rights law is that – because it is States who are in a position to violate individuals’ freedoms – respect for those freedoms may be hard to come by without international consensus and oversight. That is, a State which does not guarantee basic freedoms to its citizens is unlikely to punish or correct its own behavior, particularly in the absence of international consensus as to the substance of those freedoms and a binding commitment to the international community to respect them.

States’ human rights duties have come to include positive and negative obligations. This means that, in limited circumstances, States may have a duty to take proactive steps to protect individuals’ rights (rather than merely refraining from directly violating those rights), including from non-State action. In addition, demand for protections beyond the traditional civil and political sphere has increased the number and variety of interests which are recognized as rights, particularly in the area of economic, social and cultural concerns. As such, we refer to States’ duties to: respect, protect, and fulfill the enjoyment of human rights.

While international human rights courts and monitoring bodies oversee States’ implementation of international human rights treaties, a variety of other sources are also relevant to the determination of individuals’ rights and States’ obligations. These include the judicial and quasi-judicial decisions of international and domestic courts on international human rights law or its domestic equivalents; the decisions of domestic and international courts on the related (but distinct) subject of international criminal law; and analysis and commentary by scholars and others. Of course, a necessary component of human rights protection is the factual research identifying the conditions which may constitute violations, which is conducted by intergovernmental organizations, as well as by civil society.

International human rights law is dynamic and its boundaries are daily being pushed in new directions. IJRC’s News Room can help readers keep up with developments in the law, its interpretation, and the individuals and communities who are affected.

THE INTERNATIONAL HUMAN RIGHTS FRAMEWORK

In the post-World War II period, international consensus crystallized around the need to identify the individual rights and liberties which all governments should respect, and to establish mechanisms for both promoting States’ adherence to their human rights obligations and for addressing serious breaches. Thus, in the decade following the war, national governments cooperated in the establishment of the United Nations (UN),[1] the Organization of American States (OAS),[2] and the Council of Europe (COE),[3] each including among its purposes the advancement of human rights.

These intergovernmental organizations then prepared non-binding declarations or binding treaties which spelled out the specific liberties understood to be human rights, including the Universal Declaration of Human Rights,[4] American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man,[5] and the European Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms.[6] By the end of the 1950s, these three systems (United Nations, Inter-American and European) had each established mechanisms for the promotion and protection of human rights, which included the (former) UN Commission on Human Rights, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, the (former) European Commission of Human Rights, and the European Court of Human Rights.

In subsequent decades, each oversaw the drafting of human rights agreements on specific topics[7] and created additional oversight mechanisms, which now include the United Nations treaty bodies and Universal Periodic Review, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, and the European Committee of Social Rights.

More recently, other intergovernmental organizations have also established, or begun to establish, regional human rights treaties and monitoring mechanisms. In Africa, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights and the African Court on Human and Peoples’ Rights monitor State compliance with the African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights.[8] The decline of the Soviet Union spurred the formation of the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE) which recognized dialogue on human rights, political and military relations, and economic development as being equally important to sustained peace and stability across Europe and the (former) Soviet States.[9] In Southeast Asia, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) has recently created the ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights,[10] and the League of Arab States in 2009 created the Arab Human Rights Committee.[11]

In addition, the UN, Inter-American, and African systems appoint individual experts to monitor human rights conditions in a range of priority areas, such as arbitrary detention and discrimination. These experts are often called rapporteurs, and they carry out their work by receiving information from civil society, visiting countries, and reporting on human rights conditions and the ways in which they violate or comply with international norms. The Council of Europe’s Commissioner for Human Rights fulfills a similar role, although his mandate is not issue-specific.[12] The UN High Commissioner for Human Rights supports and coordinates the UN’s human rights activities, in addition to independently addressing issues of concern through country visits, dialogue with stakeholders, and public statements, much as rapporteurs do.[13]

HUMAN RIGHTS BODIES’ FUNCTIONS

One can think of the different mechanisms for the protection of human rights as overlapping umbrellas of distinct sizes, positioned around the globe. The different umbrellas are made up of the courts and monitoring bodies of the following universal and regional human rights systems:

- United Nations

- UN Human Rights Council

- human rights treaty bodies

- independent experts known as “special procedures“

- Universal Periodic Review

- Africa

- the Americas

- Europe

- the Middle East & North Africa

- Southeast Asia

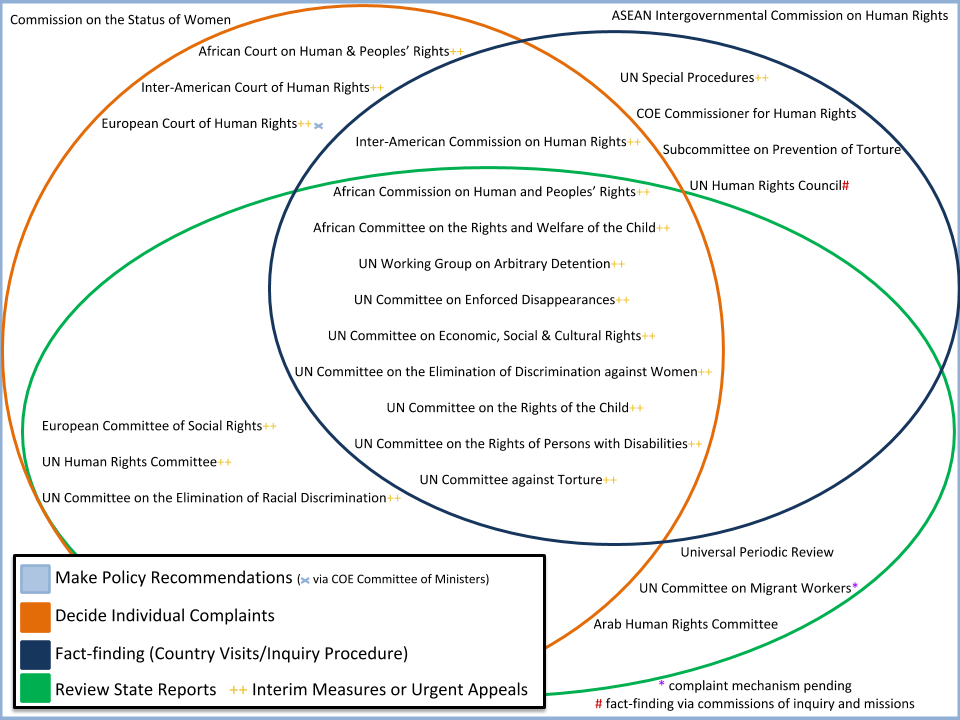

These human rights bodies each have different functions and jurisdiction, as shown in the below diagram and explanatory chart of human rights mechanisms’ competencies. In general, these mechanisms’ responsibilities may include: deciding complaints against States, engaging in independent monitoring through country visits and reporting, and reviewing States’ reports on their own compliance with human rights standards.

In addition, other intergovernmental or political bodies engage in standard-setting, inter-State dialogue, monitoring, or promotion of human rights; such bodies include the UN Human Rights Council, ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights, and the Commission on the Status of Women.

Click on the image below to open a PDF version of the diagram with hyperlinks to each body.

Other International Courts & Monitoring Bodies

In addition, a variety of other international bodies outside of what is traditionally referred to as the “international human rights framework” also play a role in addressing human rights violations.

For example, States may bring complaints against other States before the International Court of Justice, which from time to time decides cases involving individuals’ human rights from the standpoint of one State’s allegation that another violated the terms of an international agreement (such as by not affording its nationals access to consular representatives when they were detained in the second State). The International Labour Organization (ILO) also oversees States’ compliance with international labor standards, including by receiving inter-State complaints concerning alleged violations of ILO conventions.

Further, individuals (as opposed to States) may be criminally prosecuted for violations of international humanitarian law or international criminal law or of jus cogens norms of international law, or may be sued civilly under domestic law. The International Criminal Court, International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia, and a number of internationalized criminal tribunals undertake such prosecutions.

A number of regional courts created through economic integration or development agreements have jurisdiction to adjudicate disputes related to human rights. These courts and tribunals of regional economic communities operate in subregions of Africa, the Americas, and Europe.

Finally, national, or “domestic,” bodies also play an important role in implementing and enforcing international human rights standards, including through national human rights institutions (NHRIs), domestic civil and criminal legal proceedings, the exercise of universal jurisdiction, and truth and reconciliation commissions.

CROSS-FERTILIZATION & COMPETING JURISDICTION

These overlapping umbrellas sometimes mean that a particular State will participate in, and report to, several supranational human rights bodies. For example, in the Western Hemisphere, all 35 independent countries are members of the Organization of American States and, as such, have signed the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man, under which complaints can be brought against them before the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. In addition, each of these countries may or may not have ratified one or more of the core UN human rights treaties overseen by a treaty body – such as the Committee Against Torture – that accepts individual complaints. Additionally, each State may have agreed to bring inter-State disputes arising under a specific treaty, such as the Vienna Convention on Consular Relations, to the International Court of Justice. Further, any of these States may also be a party to the Rome Statute, meaning it is obligated to cooperate with the International Criminal Court in the prosecution of individuals suspected of committing genocide, crimes against humanity, war crimes or (in the future) aggression.

Although each of the various human rights bodies operates independently from the others, under a specific mandate and within the scope of its particular treaties, the provisions of the regional and universal human rights treaties are often highly similar. As such, each tribunal often looks to the jurisprudence of the others when deciding novel or delicate questions. Tribunals also look to other bodies’ interpretations when another treaty exists (typically a universal treaty) that is more specific or germane to the topic at hand, such as when tribunals look to the International Labour Organization conventions in interpreting the scope of labor rights.

However, this does not mean that the various tribunals have reached consistent conclusions on similar matters. Neither does it mean that the jurisprudence of each body is as developed as the rest. Some tribunals have decades’ more experience than others; some, such as the European Court of Human Rights, are so well-known in their regions that they are inundated with claims, while others receive only a handful per year.

Further, the fact that various systems exist does not mean that an individual complainant will be able to obtain redress before any or all of them. Indeed, most judicial and quasi-judicial human rights bodies will only examine an individual complaint if it has not been previously determined by another international body. Finally, each body’s jurisdiction is subject to distinct geographical, temporal and substantive limitations.

Accordingly, the layers of protection vary from State to State, depending on the existence of a regional human rights system and each State’s ratification of regional and universal instruments. Use of one system over another will depend not only on State membership, but also on which body has produced more favorable caselaw, the reparations and other outcomes available at each, and practical considerations such as case processing time and backlogs.

If you have a question about the international human rights framework, would like research assistance, or seek advice regarding a specific complaint, please contact us.

[1] Charter of the United Nations, Jun. 26, 1945, 1 U.N.T.S. XVI [hereinafter UN Charter].

[2] See Charter of the Organization of American States, April 30, 1948, 119 U.N.T.S. 3, entered into force Dec. 13, 1951; amended by the protocols of Buenos Aires, Cartagena, Washington and Managua [hereinafter OAS Charter].

[3] Statute of the Council of Europe, May 5, 1949, 87 U.N.T.S. 103, E.T.S. 1.

[4] Universal Declaration of Human Rights, G.A. Res. 217A (III), U.N. Doc. A/810 at 71 (1948).

[5] American Declaration on the Rights and Duties of Man, May 2, 1948, O.A.S. Res. XXX, reprinted in Basic Documents Pertaining to Human Rights in the Inter-American System, OAS/Ser.L/V/I.4 Rev. 9 (2003); 43 AJIL Supp. 133 (1949).

[6] Convention for the Protection of Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms, Nov. 4, 1950, ETS 5; 213 UNTS 221, entered into force Sept. 3, 1953 [hereinafter European Convention on Human Rights].

[7] See, e.g. ,International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, Dec. 16, 1966, 999 U.N.T.S. 171; S. Exec. Doc. E, 95-2 (1978); S. Treaty Doc. 95-20, 6 I.L.M. 368 (1967); International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination, Dec. 21, 1965, S. Exec. Doc. C, 95-2 (1978); S. Treaty Doc. 95-18; 660 U.N.T.S. 195, 212; American Convention on Human Rights, Nov. 21, 1969, O.A.S. T.S. No. 36; 1144 U.N.T.S. 143; S. Treaty Doc. No. 95-21, 9 I.L.M. 99(1969); Inter-American Convention to Prevent and Punish Torture, O.A.S. Treaty Series No. 67, entered into force Feb. 28, 1987, reprinted in Basic Documents Pertaining to Human Rights in the Inter-American System, OEA/Ser.L.V/II.82 doc. 6 rev.1 at 83, 25 I.L.M. 519 (1992); European Convention for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Oct. 10, 1994, E.T.S. 126, entered into force Feb. 1, 1989.

[8] African Charter on Human and Peoples’ Rights, June 27, 1981, 1520 U.N.T.S. 217, 245; 21 I.L.M. 58, 59 (1982).

[9] Charter of Paris for a New Europe, Paris, 21 November 1990, 2nd Summit of Heads of State or Government, Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE); and Budapest Summit Declaration: Towards a Genuine Partnership for a New Era, Budapest, 21 December 1994, 4th Summit of Heads of State or Government, Conference on Security and Co-operation in Europe (CSCE). For details on origins of the OSCE, see http://www.osce.org/who.

[10] See ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights, Terms of Reference, http://www.asean.org/publications/TOR-of-AICHR.pdf.

[11] See Mervat Rishmawi, The Arab Charter on Human Rights and the League of Arab States: An Update, Human Rights L. Rev.10:1 (2010), 169-178.

[12] See Council of Europe, Commissioner for Human Rights, Mandate, http://www.coe.int/t/commissioner/Activities/mandate_en.asp.

[13] See Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, About Us, Who We Are, http://www.ohchr.org/EN/AboutUs/Pages/WhoWeAre.aspx.