In a written and video statement made public on Monday, March 11, 2013, International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor Fatou Bensouda announced she would be withdrawing all charges against Francis Muthaura arising out of Kenya’s 2007 and 2008 post-election violence. Muthaura, Kenya’s former civil service chief, was accused of committing crimes against humanity, including murder and rape. Bensouda’s decision marks the first time charges have been withdrawn against an ICC defendant scheduled for trial. Some observers see the Kenya cases as problematic, but Prosecutor Bensouda has won praise for what is seen as a difficult but necessary decision which reflects well on her office’s credibility and professionalism. [Justice in Conflict]

In a written and video statement made public on Monday, March 11, 2013, International Criminal Court (ICC) prosecutor Fatou Bensouda announced she would be withdrawing all charges against Francis Muthaura arising out of Kenya’s 2007 and 2008 post-election violence. Muthaura, Kenya’s former civil service chief, was accused of committing crimes against humanity, including murder and rape. Bensouda’s decision marks the first time charges have been withdrawn against an ICC defendant scheduled for trial. Some observers see the Kenya cases as problematic, but Prosecutor Bensouda has won praise for what is seen as a difficult but necessary decision which reflects well on her office’s credibility and professionalism. [Justice in Conflict]

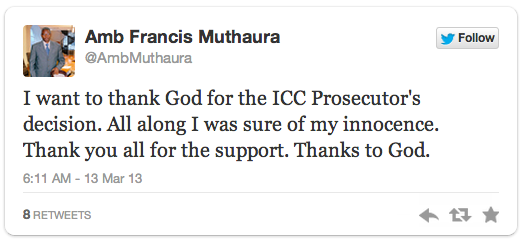

Via his Twitter account and a published statement, Muthaura expressed his gratitude for the prosecutor’s decision and reiterated his innocence, but said that the experience of being investigated and charged by the ICC broke his heart.

Background and Charges against Muthaura

Francis Muthaura is a senior advisor to outgoing Kenyan President Mwai Kibaki and, according to the BBC, is seen as “one of the most powerful unelected figures in the country.” ICC prosecutors originally believed that Muthaura was responsible for a January 2008 attack against the civilian residents of Nakuru and Naivasha that resulted in a large number of killings, displacement of thousands of people, rape, severe physical injuries and mental suffering.” [ICC]

During the highly contested elections, Kenyan opposition members disputed the outcome of a presidential vote, unleashing the worst unrest in the east African country since independence in 1963. More than 663,000 people were displaced in Kenya’s Rift Valley after fights between rival supporters, prosecutors said, when politically motivated riots soon turned into ethnic killings, which in turn sparked further reprisals. [Al Jazeera]

Prosecutor Bensouda decided the case against Muthaura could not be tried due to the fact that it was flawed— key witnesses were killed, had gone missing, or were bribed. In Monday’s statement, Bensouda outlined some of the “severe challenges” the ICC has faced in the investigation of Muthaur, including:

-

the fact that several people who may have provided important evidence regarding Mr. Muthaura’s actions, have died, while others are too afraid to testify for the Prosecution.

-

the disappointing fact that the Government of Kenya failed to provide my Office with important evidence, and failed to facilitate our access to critical witnesses who may have shed light on the Muthaura case.

-

the fact that we have decided to drop the key witness against Mr. Muthaura after this witness recanted a crucial part of his evidence, and admitted to us that he had accepted bribes.

Until the charges were dropped, the ICC prosecutor planned to try Mr. Muthaura as an indirect co-perpetrator pursuant to Article 25 (individual criminal responsibility) of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court (Rome Statute) for the crimes against humanity of:

- Murder (article 7(l)(a));

- Deportation or forcible transfer (article 7(l)(d));

- Rape (article 7(l)(g));

- Persecution (article 7(l)(h)); and

- Other inhumane acts (article 7(l)(k)).

Article 7 of the Rome Statue defines crimes against humanity as “any of the [listed] acts when committed as part of a widespread or systematic attack directed against any civilian population, with knowledge of the attack.”

Prosecution of Kenyatta

Muthaura was to be prosecuted jointly with Kenya’s incoming president Uhuru Kenyatta, elected last week in a process praised by the African Union. Like Muthaura, Kenyatta is accused of murder, deportation or forcible transfer, rape, persecution and other inhumane acts. The ICC prosecutor alleges that Kenyatta, who was a leader within the Party of National Unity at the time, provided “institutional support, on behalf of the [Party of National Unity] Coalition, to secure: (i) the agreement with the Mungiki [criminal organization allegedly responsible for attacks against non-Kikuyu individuals perceived as supporting the Orange Democratic movement] for the purpose of the commission of the crimes; and (ii) the execution on the ground of the common plan by the Mungiki in Nakuru and Naivasha.” See ICC, Case Information Sheet, p. 2.

In response to speculation that the charges against Kenyatta will also be withdrawn, ICC Prosecutor Bensouda stated, “[l]et me be absolutely clear on one point… [t]he decision to drop charges against Muthaura “does not apply to any other case.” While Kenyatta’s lawyer alleges that the ICC’s case against his client is “utterly flawed,” Bensouda stressed that her case against Kenyatta would continue. The ICC judges, however, did not appear so sure. Presiding Judge Kuniko Ozaki said the announcement “will have consequences not just for the case against Mr. Muthaura, but also in some way Mr. Kenyatta.” [Washington Post] Kenyatta’s trial has been postponed until July 2013.

Other Pending Kenya Prosecutions

The other Kenya-related ICC case, which is in the trial phase, involves Kenyatta’s running mate William Samoei Ruto. See ICC, Situation in the Republic of Kenya The case, The Prosecutor v. William Samoei Ruto and Joshua Arap Sang, concerns two defendants allegedly responsible for murder, deportation or forcible transfer of population, and persecution. The ICC Pre-Trial Chamber II found that there are substantial grounds to believe that immediately after the announcement of the results of the 2007 presidential election, an attack was carried out – following a unified, concerted and pre-determined strategy – by different groups of people that resulted in the deaths of 230 people. See ICC, Case Information Sheet, p. 2. During that time, 505 people were injured, while over 5,000 were displaced. Id.

According to the prosecutor, defendant William Ruto’s was more hands-on than than Kenyatta in that he allegedly:

(i) overall planned and was responsible for the implementation of the common plan in the entire Rift Valley;

(ii) created a network of perpetrators to support the implementation of the common plan;

(iii) directly negotiated or supervised the purchase of guns and crude weapons;

(iv) gave instructions to the perpetrators as to who they had to kill and displace and whose property they had to destroy; and

(v) established a rewarding mechanism with fixed amounts of money to be paid to the perpetrators upon the successful murder of PNU supporters or destruction of their properties.

See ICC, Case Information Sheet, p. 2. The prosecutor’s office states that defendant Joshua Sang “by virtue of his influence in his capacity as a key Kass FM radio broadcaster, allegedly contributed in implementation of the common plan.” Id. The trial is scheduled to start on May 28, 2013; however, the defendants are not in the custody of the Court.

With regard to several of the Kenyan suspects, the Court has determined the evidence is insufficient to proceed to trial on the original charges. In January 2013, the ICC Pre-Trial Chamber II declined to confirm the charges against Kenyatta and Muthaura’s former co-defendant, Mohammed Hussein Ali, former Commissioner of the Kenya Police. The Pre-Trial Chamber II also declined to confirm the charges against Henry Kiprono Kosgey, a former member of parliament, who was to be tried with Ruto. While the chamber confirmed charges against Ruto and Kosgey’s co-defendant Joshua Arap Sang, it did so under a different theory of responsibility, finding sufficient grounds to try him for “contributing,” as opposed to “committing” the alleged crimes. Cf. Rome Statute, art. 25(3)(a) and (d).

Some critics have pointed out the problems of allowing ICC defendants to remain at large with the freedom to attack the credibility of the court or potentially intimidate witnesses. And, the problem highlighted by Prosecutor Bensouda of inadequate cooperation by the Kenyan government is unlikely to improve with the new administration.

The Los Angeles Times quotes Gladwell Otieno, a representative of the African Center for Open Governance as saying, “The issue here is that you have a government that is not willing to live up to its international obligations. Basically the government — by not cooperating and blocking the ICC at every turn — is breaking those agreements.” [LA Times] The ICC’s credibility is also at stake, and failure to convict any of the Kenyan defendants could encourage other high-level officials, like Sudan’s President Bashir, who are refusing to cooperate with the court. [LA Times]