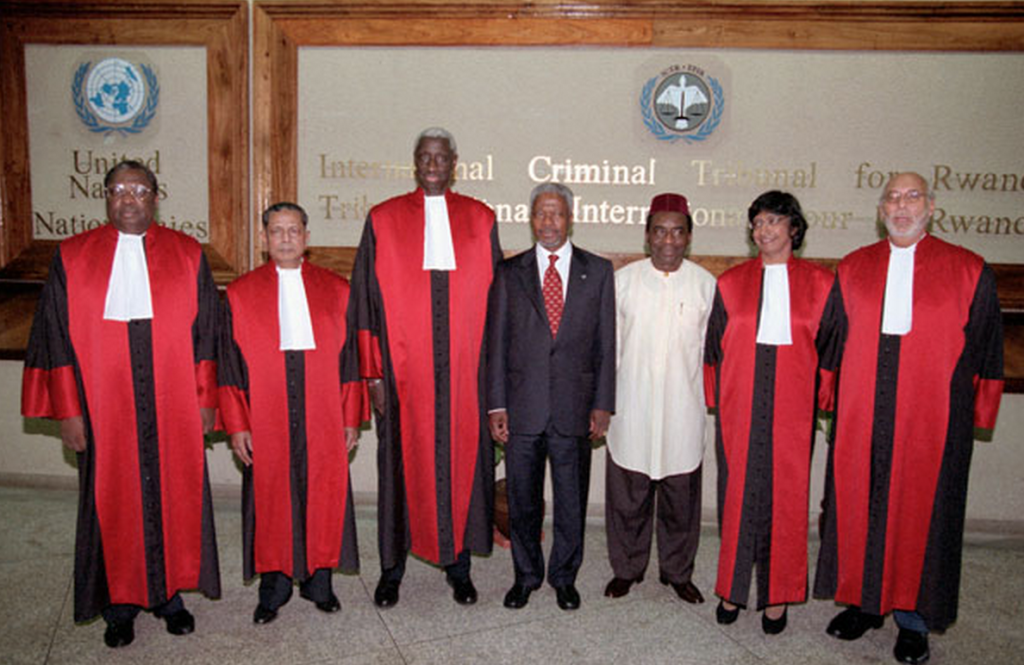

Credit: UN

After more than 20 years of prosecuting those most responsible for the Rwandan genocide of 1994, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) has issued its final judgment and closed its doors. [The Citizen] In its forty-fifth and final judgment, delivered on December 14, 2015, the Appeals Chamber decided appeals from six defendants previously convicted by the Trial Chamber. [BBC] While it confirmed the guilty verdicts in the “Butare Six” case, the Appeals Chamber found the sentences imposed to be excessive; it ordered the release Sylvain Nsabimana and Joseph Kanyabashi, and granted sentence reductions to the remaining four appellants, Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, Arsène Shalom Ntahobali, Alphonse Nteziryayo, and Élie Ndayambaje. See ICTR, Prosecutor v. Nyiramasuhuko et al. (Butare), Case ICTR-98-42, Appeals Chamber Judgment, 14 December 2015. With this case finalized, the ICTR formally closed at the end of 2015. Since it began operating in 1995, the ICTR has indicted a total of 93 people – and convicted 61 – on charges of war crimes, crimes against humanity, and genocide. See ICTR, The ICTR in Brief. While sometimes criticized for doing too little, too slowly, the ICTR has contributed to justice and accountability for Rwandans and to the development of international criminal law.

The Butare Trial and Appeals

In 2011, the ICTR Trial Chamber II issued its judgment and verdict concerning the six defendants prosecuted in connection with acts of genocide and rape in the Butare district. See ICTR, Prosecutor v. Nyiramasuhuko et al., Case ICTR-98-42, Trial Chamber II Judgment, 24 June 2011. The Trial Chambers first considered the appellants’ roles in the 1994 genocide. Sylvain Nsabimana was préfet (governor) of Butare until being succeeded by Alphonse Nteziryayo and, in this role, both contributed to forming and executing the plan to eliminate the Tutsi population. Joseph Kanyabashi was bourgmestre (mayor) of Ngoma commune in Butare and was accused of contributing to the genocide by distributing arms and giving speeches inciting violence. As Minister for the Family and Woman’s Affairs, Pauline Nyiramasuhuko, was directly involved in sociopolitical policies and, as such, participated in the development of the plan to exterminate Tutsis. Her son, Arsène Shalom Ntahobali, was a leader of a unit of the Interahamwe (Hutu extremist militia), over which he exercised authority and control. Élie Ndayambaje was mayor of Muganza commune in Butare, where he had executive power and implemented the genocidal policies. See Trial Watch, Profiles.

The Trial Chamber found Nsabimana, Kanyabashi, Nyiramasuhuko, Ntahobali, and Ndayambaje guilty of genocide, crimes against humanity, and one or more serious violations of Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions (war crimes). It also convicted Nyiramasuhuko of conspiracy to commit genocide and convicted Nteziryayo, Kanyabashi, and Ndayambaje of direct and public incitement to commit genocide. See ICTR, Prosecutor v. Nyiramasuhuko et al., Trial Chamber II Judgment,

The Appeals Chamber considered appeals from each of the defendants, as well as an appeal from the prosecution alleging that the Trial Chamber erred in acquitting Kanyabashi of genocide and direct and public incitement to commit genocide in relation to a speech he gave. See ICTR, Prosecutor v. Nyiramasuhuko et al., Case ICTR-98-42, Summary of Appeal Judgment, 14 December 2015. The defendants each alleged various violations of their fair trial rights during the proceedings, and also challenged the grounds of their convictions and the sentences imposed. The Appeals Chamber dismissed the prosecution’s appeal and upheld the convictions, but reduced the defendants’ sentences. See id. Originally, Nyiramasuhuko, Ntahobali, and Ndayambaje were sentenced to life imprisonment; Nsabimana to 25 years; Nteziryayo to 30 years; and Kanyabashi to 35 years. Upon reducing their sentences, the Appeals Chamber ordered Nsabimana and Kanyabashi released in consideration of the time they had already spent in jail. See id.

ICTR Legacy

The ICTR was established by the United Nations (UN) Security Council in November 1994 to prosecute those responsible for genocide and other serious violations of international humanitarian law committed in Rwanda during the 1994 genocide, a civil war and ethnic cleansing of Tutsis and moderate Hutus by Hutu extremists. See UN Security Council, Resolution 995, UN Doc. S/RES/955 (1994), 8 November 1994, para. 1. ICTR was the first international tribunal to issue a verdict concerning genocide. [BBC] Over the course of its 21 years of operation, ICTR indicted 93 people, sentenced 61, acquitted 14, and heard over 3,000 witnesses’ testimony. [BBC]

With 800,000 dead in the 100-day genocide, the ICTR shared responsibility for remedying the atrocities with domestic tribunals and gacaca, informal justice mechanisms described as community courts. [News 24; Africa Research Institute] The gacaca courts were criticized for their lack of lawyers and formal judicial procedure, which many argued failed to meet international standards; however, the community trials have been praised for doing much to meet the need for truth and justice, handling as many as one million cases. [Africa Research Institute]

Among other criticisms, some suggest that the ICTR did share enough of the burden, with the gacaca courts resolving the bulk of the cases. [Justice Hub] The ICTR has also been accused of being inefficient, expensive, and biased because it only dealt with crimes committed by the Hutus and not the members of the Tutsi party now in power. [New York Times] The Butare trial itself has been described as the “longest, largest, and probably most expensive” international prosecution ever. [IPS] Debate continues over what should happen to those who have been acquitted by the tribunal, as well as how to proceed regarding fugitives who have yet to be tried for their crimes in relation to the genocide. However, the ICTR remains an important institution for peace and justice in Rwanda and a primary example of the expanded role of international justice in documenting and assigning responsibility for atrocities, as well as, hopefully, deterring their commission in the future.

Next Steps for Rwanda

The Residual Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT), established by the UN and headquartered in the Hague, will continue to operate from an office in Arusha to conclude any unfinished ICTR business and support domestic prosecutions of criminals involved in the 1994 genocide. [New York Times] In particular, the MICT will support efforts to bring to justice eight Rwandan fugitives who continue to be at large, one of whom was captured in the Democratic Republic of the Congo last month. [New York Times]

The UN plans to transfer the ICTR archives to a smaller facility in Tanzania; however, the Rwandan government is demanding that the archive be brought there. [New Times] The Rwandan government argues that the ICTR sets precedent for Rwanda and its judiciary is entitled to the records as a judicial tool. [New Times] Moreover, the national authorities raised concerns regarding enforcement of the ICTR’s sentences, which they say could be better addressed through possession of the archives. [New Times]

Additional Information

For additional information on international criminal law, the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda, and the new database for accessing ICTR records, visit IJRC’s Online Resource Hub.