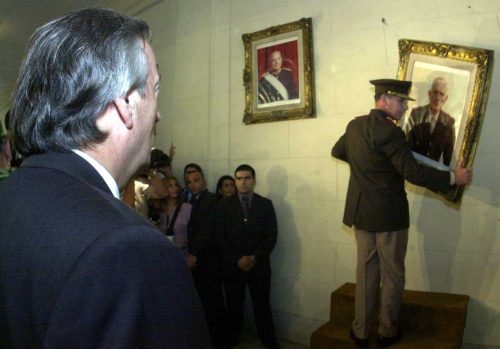

Credit: Presidency of Argentina

An Argentine court has convicted and sentenced former dictator Reynaldo Bignone and 14 other former Argentine military officers of crimes against humanity for their roles in Operation Condor, a transnational conspiracy behind the kidnapping, torture, killing, and forced disappearance of hundreds of political dissidents during the 1970s and 1980s. [NYT; CIJ] Bignone was convicted of participating in an illicit association, kidnapping, and the forced disappearance of over 100 people. [Telegraph: Operation Condor] The ruling is the first time a court in the region has publicly determined that dictators in Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay collaborated in the cross-border conspiracy to eliminate leftist dissidents, some of whom had previously evaded their reach by fleeing to neighboring countries. [NYT] Additionally, the case is a rare example of a domestic court’s prosecution of a former head of state for transnational crimes, and is also noteworthy because the defendants were convicted on the basis of their participation in the international conspiracy rather than on individual criminal charges. [NPR]

Recent Convictions and Sentencing

A four-judge panel in Argentina’s federal court brought the 13-year trial to a close on May 27, 2016 when it sentenced 15 and cleared two of the remaining original 32 defendants in the case. The 105 identified victims of kidnapping, murder, and forced disappearance were nationals of Uruguay, Chile, Paraguay, Bolivia, and Argentina. [Clarin (Spanish); CIJ (Spanish)] Among those convicted, Santiago Omar Riveros, the former director of the military institute, and former colonel Manual Cordero Piacentini of Uruguay – the first Uruguayan officer tried for torture in Argentina – received the longest sentences, of 25 years in prison, for their roles in Operation Condor. [Clarin; BBC: Operation Condor] Bignone was sentenced to 20 years in prison. In addition, most of the defendants, including Bignone, have been disqualified from holding public office for specific amounts of time, ranging from 24 years to a life ban. [Clarin; CIJ]

Accountability for Operation Condor at the Domestic Level in Argentina

Argentina initially faced obstacles in holding individuals accountable for the crimes committed during Operation Condor, including difficulty accessing evidence, but has made strides in holding former military and political leaders accountable. An investigation into the international conspiracy first began in the 1990s, when an Argentine amnesty law enacted by Bignone himself still sheltered many of the accused from liability for human rights crimes. [Telegraph: Operation Condor] The Argentine Supreme Court overturned the amnesty law in 2005, paving the way for Bignone’s conviction. [Telegraph: Operation Condor] However, several of those most responsible for the abuses of the 1970s and 1980s have since died. [BBC: Condenas (Spanish)]

Bignone, who is currently serving a life sentence for the kidnapping and murder of political dissidents, including a former congressman, has been convicted of crimes related to Operation Condor several times in the last six years. [BBC: Bignone] In 2010, Bignone was sentenced to 25 years in prison for his role in 56 cases of murder, torture, and deprivation in Campo de Mayo, the army base that doubled as one of Argentina’s largest torture centers. See International Crimes Database, Reynaldo Bignone Causa “Campo de Mayo”. In 2012, he was convicted of orchestrating the abduction of 20 babies from leftist opponents during the dictatorship and sentenced to another 15 years for overseeing the kidnappings. [Telegraph: Baby Thefts] Just two years ago, Bignone received an additional 23 years for abducting and torturing more than 30 factory workers in an effort to eliminate trade union demands. [BBC: Sentence] In addition to Bignone, in the last 10 years, the Argentine courts have convicted 666 individuals of crimes associated with Operation Condor. [NYT]

The availability of a large amount of documentary evidence from the United States, which provided some support to the conspiracy, has assisted the prosecutions of these crimes, particularly in the trial decided on May 27. [BBC: Operation Condor; Guardian] The declassified documents included an FBI agent’s cable that thoroughly described the scheme to share intelligence and silence leftists across the continent. [Telegraph: Operation Condor] President Obama recently ordered the further declassification of American records that could unearth what the United States government knew about Argentina’s “dirty war,” but it is unclear when the declassification will take place. [NYT]

Accountability for Operation Condor at the International Level

The Inter-American Court of Human Rights (IACtHR) has previously ruled on human rights violations arising out of Operation Condor. The first IACtHR case involving evidence on the existence of the conspiracy was Goiburú et al. v. Paraguay in which the IACtHR acknowledged the existence of Operation Condor and found violations of the rights to liberty, humane treatment, life, and fair trial under the American Convention on Human Rights for the forced disappearance, torture, and murder of the victims. See I/A Court H.R., Goiburú et al. v. Paraguay. Merits, Reparations, and Costs. Judgment of September 22, 2006. Series C No. 153. Dr. Agustín Goiburú, a victim cited in the case, was openly critical of the government and left his home country of Paraguay for Argentina in an attempt to escape harassment, but in Argentina, he was kidnapped twice, sent back to Paraguay to be held in detention, and forcibly disappeared. The other victims’ situations considered by the Court followed similar patterns involving forced disappearances in relation to Operation Condor. See id. at paras. 61(14)- 61(50).

A subsequent IACtHR decision, Gelman v. Uruguay, also took into account the context of Operation Condor and found violations of the rights to life, humane treatment, and liberty in the context of forced disappearances and murder coordinated across borders. See I/A Court H.R., Gelman v. Uruguay. Merits and Reparations. Judgment of 24 February 2011. Series C No. 221. In 1976, María Claudia García Iruretagoyena Casinelli and her husband, Marcelo Ariel Gelman Schubaroff, were detained by Argentinian and Uruguayan officials. Iruretagoyena was then transferred to Uruguay and was later killed, and Gelman was killed while still in Argentina. See id. at paras. 73-89.

Background on Operation Condor

Operation Condor entailed the cross-border collaboration of several South American military dictatorships with the goal of annihilating political opposition and Marxist ideology in the region. [BBC: Operation Condor] Begun in 1975 by Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet, the operation continued into the following decade. [Washington Post] Leftist opponents of the dictators suffered interrogation and torture in clandestine prisons, such as Automotores Orletti, a repair shop in Buenos Aires where Piacentini would torture detainees. [BBC: Operation Condor; Washington Post] Some of the victims’ bodies from Automotores Orletti were hidden in oil drums sealed with concrete. [NYT]

In addition to crossing national borders in South America, Operation Condor’s scope reached North America. In 1976, Chilean agents carrying out the conspiracy orchestrated a car bombing in Washington, D.C. that killed former Chilean ambassador Orlando Letelier and U.S. citizen Ronni Moffit. Operation Condor also reached Europe; individuals involved in carrying out the conspiracy followed exiles there in an attempt to kill or forcibly disappear them. [Telegraph: Operation Condor]

The Argentine court’s recent holding has been commended by human rights groups. Jose Miguel Vivanco, the Americas director for Human Rights Watch, explained, “This ruling, about the coordination of military dictatorships in the Americas to commit atrocities, sets a powerful precedent to ensure that these grave human rights violations do not ever take place again in the region.” [Al Jazeera]

Additional Information

For more information on the role of national courts in human rights prosecutions and international criminal law, visit IJRC’s Online Resource Hub.